A veteran curator offers practical steps for employees across the museum.

By Mia Locks is a curator and the co-founder of Museums Moving Forward

Simone Forti, Huddle (1961). Performance. 10 min. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Committee on Media and Performance Art Funds. © 2019 The Museum of Modern Art, New York (Performance at Fondazione ICA Milano)

Simone Forti, Huddle (1961). Performance. 10 min. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Committee on Media and Performance Art Funds. © 2019 The Museum of Modern Art, New York (Performance at Fondazione ICA Milano) Despite urgent calls for more equity and accountability in the museum workplace, change is slow. If you work in a museum, like I did for more than a decade, and you are eager for change, it can be hard to feel hopeful.

But there are concrete actions you can take to create more equity—starting now. Don’t assume you need to be a director or senior leader to make a difference. Workplace change is often more impactful when driven by staff at all levels who harness their collective power.

I have been privileged to work at contemporary art museums in New York and Los Angeles with very talented people, many of whom are friends. And yet, my experience is that museums are challenging places to work. Listening to peers in other fields, it often seems that museums are somehow more trying. But why?

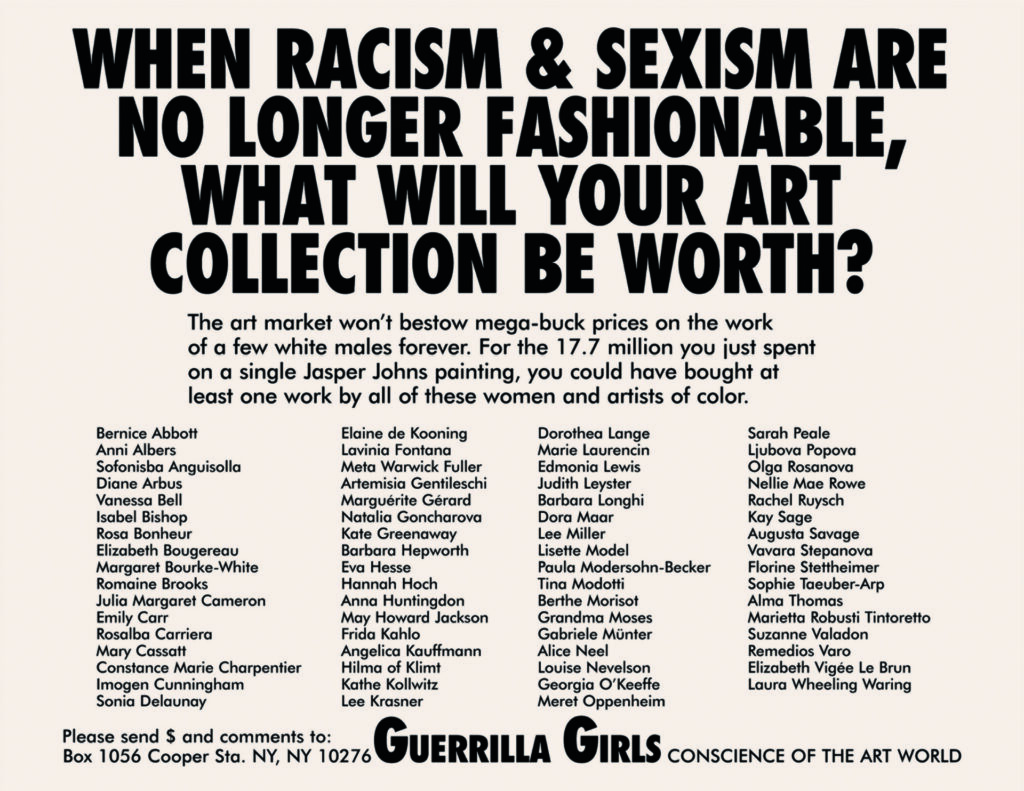

Before we get to the solutions, we need to identify some of the problems. The museum world operates within a very stubborn old power model and does not pay much attention to workplace culture. But it should. Museum culture is influenced by longstanding beliefs and structures, from the “creative genius” myth (and what this permits) to the white supremacist foundations of museums.

Many museum professionals are overworked, underpaid, and exhausted. On top of that, there are vast ideological chasms between different generations working under the same roof.

Culture impacts everything in the workplace. If healthy organizational cultures are tied to success, toxic cultures are “by far the strongest predictor of industry-adjusted attrition”—10 times more important than compensation in predicting staff turnover, according to a study in the MIT Sloan Management Review. Leading factors contributing to toxic cultures include “failure to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion” and “workers feeling disrespected.”

Equity has multiple dimensions in the 21st-century museum and encompasses more than racial and ethnic demographics. It’s not just who is at the proverbial table, but also what is being served. How are folks treating each other? What does the workplace value? When someone is “doing a good job,” what are they being lauded for?

Here are some steps I recommend to build a more equitable workplace at your museum.

1. Take Care of Your Organizational Culture.

Museum organizational models are centuries old—the Philadelphia Museum of Art, for example, opened in 1827. Stunningly, little has changed since then.

Today, one in five museum employees imagine they will quit their job within the next three years, according to a recent study by the American Alliance of Museums (AAM). Directors are aware: 45 percent of them listed “labor and skills shortage” as a disruption to bottom lines.

Likewise, the Mellon Foundation’s 2022 Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey explicitly states that “retention rates will be an important factor” in maintaining diversity, and surely morale, in the museum workplace.

Pay is a problem but “not the only issue,” according to the AAM report, which suggested the need for improving the work environment as well: “teaching managers to be good communicators and good listeners, expressing appreciation for employees, and providing opportunities for growth and advancement.”

If you want to assess your organizational culture, I don’t recommend going it alone. You will fare better working with a group of people, ideally from various museum departments. If you are part of a union, you could try that route. Or, if you are able, consider joining or even starting an ERG (employee resource group) or DEAI (diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion) committee, with the explicit goal of assessing workplace culture. If those already exist at your museum, suggest an equity assessment (you can point them to AAM’s recent “Excellence in DEAI” report that makes this suggestion explicitly).

If none of those options is available or appealing, then just commit to being a solution-seeker. We have all been in that meeting when someone throws out a seemingly radical idea, shifting the mood into a more creative place. Be that person (or be that person’s supporter). These are the seeds of change.

2. Embrace the Power of Transparency.

The word “transparency” gets thrown around a lot these days and it’s not always clear (ironically) what folks mean when they use it. It might be helpful to think of transparency as communicating as clearly and as often as possible with people regardless of their department, title, or position level.

Share the inner workings of your decision-making with your team. (If you are working with folks who were born after 1980, this is something they are likely to expect.) Obviously there are times when discretion is required, but it’s never a good idea to withhold information out of fear or expediency. Creating space for your team to ask questions isn’t only helpful for them—it’s also important for you to better understand what they are thinking and how they might need more support.

In my experience, curators are often the main hoarders of information in the museum system. I have many memories of curators refusing to share working checklists with other departments because they either felt vulnerable sharing their thinking process or they just didn’t want to move onto the next step of exhibition planning. However, the checklist is the single most important document for producing an exhibition because it impacts the jobs of almost everyone at the museum.

So, let’s work more collaboratively and make colleagues’ lives easier. I implore curators everywhere to share more of their thinking earlier in their process, even if it needs to be done with a giant disclaimer. Everyone will benefit from this—not least the exhibition and visiting publics.

3. Get Over the Old Idea of “Professionalism.”

I don’t mean that we should be wearing bikinis at the office. However, there are assumptions tied up with “professionalism” that need to be reexamined writ large if museums want to survive the sea change currently underway.

It should be expected that staff push back against norms in the workplace. Professionalism comes straight out of a time and place when workplaces were dominated by white men, and its expectations negatively impact pretty much anyone outside that group, especially women of color and young people.

If you have the impulse to police others’ professionalism when they are questioning something, focus more on what motivates their pushback—and what might come from it.

If you are doing the pushing back, try to do so with respect and an understanding that things are never black and white. People seldom thank you for your feedback, at least not in the moment, but trust that it was heard. (Or schedule a follow-up meeting if it is still on your mind.)

4. Learn From the Education Department.

Though I have worked exclusively in curatorial departments during my museum tenure, I have developed some of my most meaningful relationships with colleagues from what used to be called the education department (though recent years have seen a welcome shift to learning and/or engagement).

These are the folks who are the most directly engaged with the public on a daily basis. Their departments often operate in ways wholly different from others, adopting tools and practices from community organizing and the fields of progressive and popular education.

They might examine the power dynamics in a meeting, for instance, or readily acknowledge privilege and actively work to center the needs of the most vulnerable folks in any given room. Needless to say, the rest of the museum has a lot to learn from educators. Befriend them. Ask to attend and observe a meeting—and take note of what feels different.

(And for anyone reading this who is on a search committee for a leadership position, consider hiring folks from this department and not just curatorial.)

5. Remove as Many Obstacles as Possible for Others.

One of the best bits of professional advice I’ve received is that “a key part of your job is to remove obstacles.” This includes getting out of the way. So many museum managers fail to realize that indecision is an obstacle and that inaction prevents people from being able to do their jobs. Even if you aren’t a manager, think about the ways in which your work impacts your colleagues and remove as many obstacles and debris, big or small, as possible to create a smoother road for everyone.

6. Incorporate an Impact Check into Decision-Making.

I have seen over and again a decision-making process—around an exhibition, for example—impact a person or an entire department in unnecessarily stressful ways. A curator might want to commission an artwork that is exceedingly challenging for the registrar to manage, with the assumption that the artist and curator are the most important voices in the room.

Why not devote more time to this process? In my experience, artists often appreciate hearing from museum staff and are more than willing to collaborate. Let’s consider the real impact our decisions have on our colleagues’ labor and bandwidth—and bring their expertise to bear in finding creative solutions.

How to do this? Before a decision is made, especially big ones, stop and ask out loud, “Who is going to be most impacted by this decision?” Literally, ask the room this question. If possible, invite those in the workplace who are most affected into the discussion and incorporate their concerns as much as possible.

7. Update the Definition of High Performance.

While the #MeToo movement had a surprisingly short-lived impact on the museum field, one key takeaway should be that bad actors can no longer be excused by separating their work from their behavior. This should apply to workplace behavior more broadly, too. No matter how brilliant a curator might be, if they are abusive to staff then they are causing more damage to the workplace than any number of acquisitions, exhibitions, or essays can repair.

“Toxic rock stars can ruin the workplace experience for most employees, but they’re particularly harmful to women of color,” Deepa Purushothaman and Lisen Stromberg write in an April 2022 article published in the Harvard Business Review. “The cultures that enable them are key factors driving women of color to leave their workplaces.”

What to do? A new, comprehensive assessment of performance that reflects a person’s treatment of others might begin at the director level. All managers need to be reviewed not just for their ability to create results, but also for their treatment of others and ability to support and unlock potential, especially for women and people of color.

All promotions, and especially those in management positions, should be tied to the person’s ability to contribute to a healthy culture, to support more collaboration, not just look out for their own projects. What if we measured a manager’s success by the success of their direct reports? Or what if an exhibition’s success were not measured merely by attendance numbers or press, but by the mood and morale of the team who produced it?

At the very least, notice when someone on your team is readily supporting others and putting the group’s interests over their own personal gain, and make a point to tell them you see what they are doing and value it.

8. Gather More Data and Talk About It More Often.

Finally, it’s time for museums to embrace data collection beyond audience research. I understand the larger and wealthier museums have begun doing this, but it needs to be standard practice. AAM, which oversees the museum accreditation process, is updating its standards to include DEAI and they note equity as something measurable in order to achieve excellence: “equity requires deliberate attention to internal metrics.”

Where to start? It doesn’t need to be overly ambitious. Just focus on something that feels important to you. Collect as much information as you can to assess where you are (this can take a while because it is not always easy to get data) and set some goals for where you’d like to be in one year, three years, and five years.

If it feels too difficult to start gathering your own data internally, you can advocate for participating in existing data studies on museum equity like the aforementioned staff demographic study conducted by Mellon. Or newer studies conducted by folks like Black Trustee Alliance or Burns Halperin Report, which measure board and program equity, respectively. Or get involved with Museums Moving Forward (MMF), a staff-driven research initiative to measure equity inside museum workplaces, of which I am a co-founder. MMF just closed the data collection period for its first cycle of a new data study focused on workplace equity and organizational culture in U.S. art museums.

The throughline here is that museum workplaces need to be prioritizing the collective over the individual at every possible turn. There are emerging forms of leadership in the field that are already having a catalytic impact and redistributing power as I write this. If we don’t embrace these changes and learn how to integrate them into the existing system, then I fear museums will fail to survive in the long-term. They will fail to be culturally relevant. They will fail to attract and retain a valuable and diverse workforce. The inequities within museum workplaces have been pervasive issues for generations and it needs to stop. The clock starts now.