This Chicago museum collects work by Black female artists at seven times the national average. But it didn’t start out that way.

By Melissa Smith

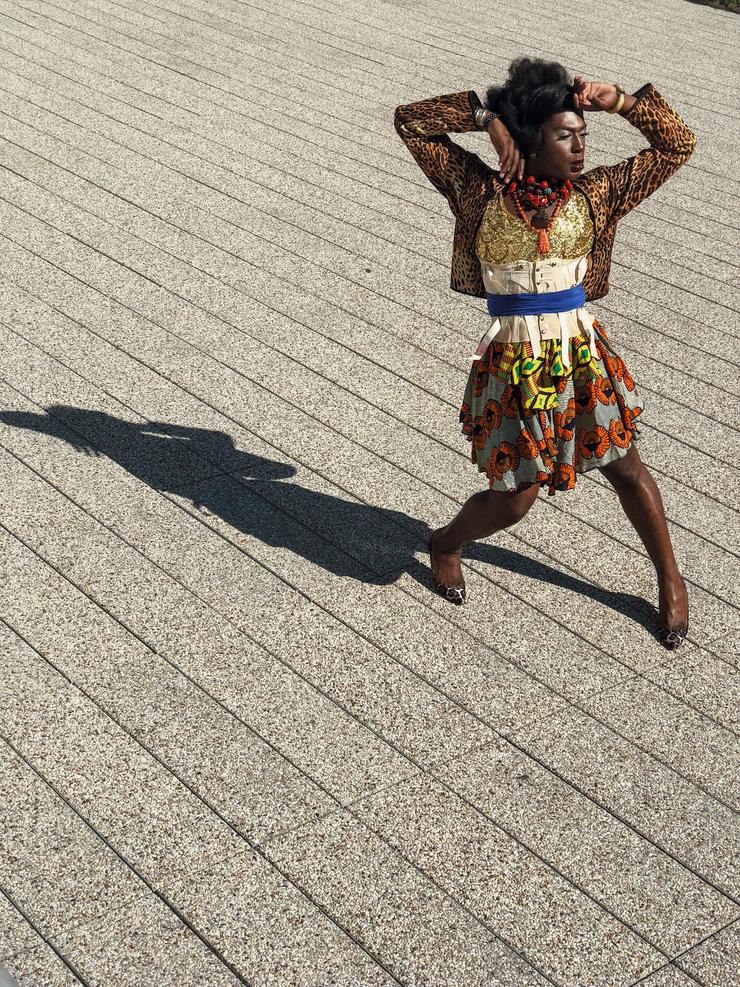

Installation view, "Duro Olowu: Seeing Chicago," 2020. Photo: Kendall McCaugherty. Courtesy of MCA Chicago.

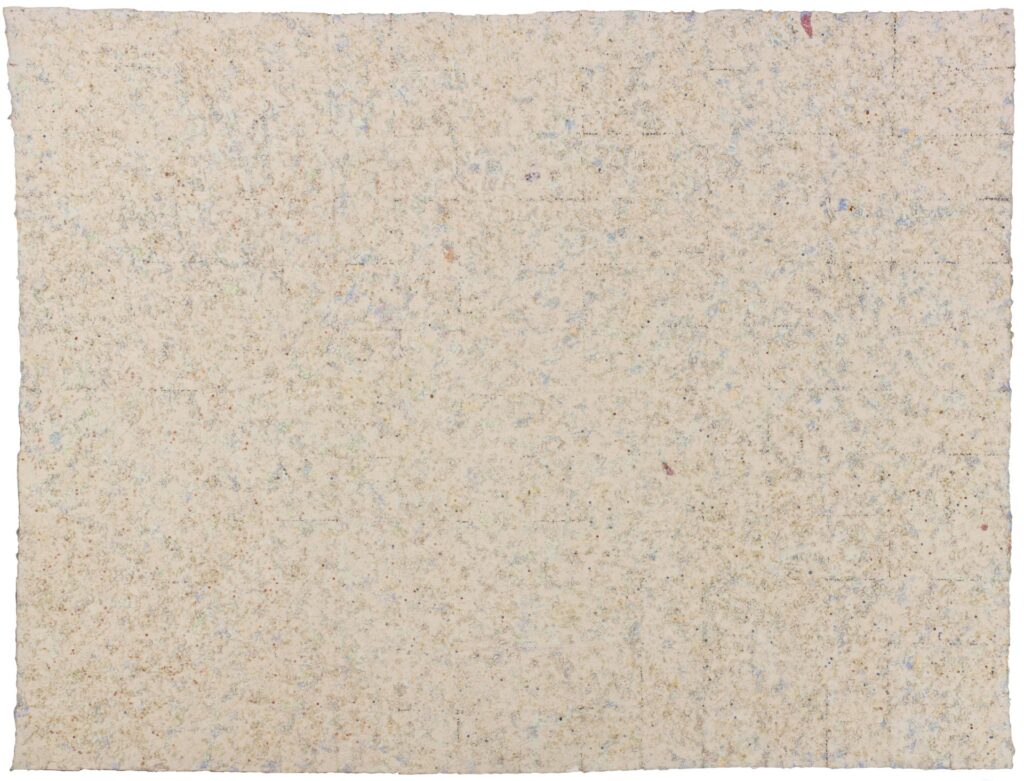

Installation view, "Duro Olowu: Seeing Chicago," 2020. Photo: Kendall McCaugherty. Courtesy of MCA Chicago.Garth Greenan was 25 when he opened his gallery. He started representing Howardena Pindell a year later, in 2012. By that point, the artist was in her late 60s. Greenan exhibited one of her major works—Untitled #20 (Dutch Wives Circled and Squared) (1978)—at the Expo Chicago art fair the following year. The beautifully textured abstract piece is composed largely of white paper dots Pindell had hole-punched and then collaged onto a large-scale canvas.

Because her work was abstract—which nearly everyone in the art world associated with white male artists at the time—even the director of the Studio Museum in Harlem didn’t know what to make of a Black woman doing it back in the ‘70s. He told Pindell to “go downtown and show with the white boys.”

Too bad nobody would really let her.

Fast forward to 2013, and the art world was trying to make up for lost time. Bringing a big mixed media work by Pindell to Expo Chicago essentially gave the MCA first dibs on a piece that Greenan was fairly confident would land in a major museum. While the work “wasn’t all that popular [among the general public],” said Greenan, Pindell was becoming “known to scholars and historians.”

Naomi Beckwith was certainly aware of who she was. She’d been introduced to Pindell’s oeuvre while working as a curator at the Studio Museum. At this point, though, Beckwith was two years into her decade-long tenure at the MCA—reporting to chief curator Michael Darling. And they both wanted that Pindell piece. Badly. So they “jumped on it,” said Greenan. But after that, they had to “rally support for it internally,” Darling recalled.

The way they did so—and have done so for scores of other works by women and artists of color—offers a roadmap other institutions can follow.

In the 12 years surveyed by the 2022 Burns Halperin Report, from 2008 to 2020, the MCA has become a leader in collecting historically underrepresented artists, with rates more than twice the national average for the work of women (25 percent of acquisitions), four times the national average for Black American artists (almost 10 percent), and seven times the national average for the work of Black American female artists (3.6 percent).

The Strategy

It took about nine months for the MCA’s curators to drum up the low six figures to buy Pindell’s piece, which officially landed in the collection in 2014–with Greenan gifting the museum a seminal video work, Free, White and 21, shortly thereafter to round out their Pindell holdings. (The museum now owns seven works by the artist.)

“The MCA already had great minimalist holdings by all the white guys, like Judd and Flavin and Ryman,” said Darling, “so we were like, ‘Hey, here’s an incredible artist that was making work at that time that connects with a lot of those same ideas—but from a female perspective; from the perspective of a woman of color dealing with racism in the art world.’”

Justifying purchases to the collection committee this way happened a lot. “We always appealed to the core of what some of its early practices were—which was looking very closely at minimalism and conceptual practices,” Beckwith said.

Diversifying the collection with pieces by Pindell and others “was a great place to start,” she continued, “because all of these people of color are doing something that looks formally or conceptually aligned with things that are already in the collection.”

In that way, they were not out to change “the soul of the institution,” she said, but simply do some “refining to the collection.”

The Chain of Command

To build a diverse collection and exhibition program “you need the full support of leadership,” Beckwith said. Indeed, curators don’t make these decisions unilaterally. They have to convince their bosses, the chief curators; and they have to convince their bosses, the directors; and all of them have to convince the ones who tend to support these things: the trustees.

The convincing gets harder when someone is proposing to do things differently than before (even if those things involve artists who should have never fallen out of the norm in the first place).

After the Pindell acquisition, Greenan pitched Beckwith and Darling on doing a Pindell solo show. They agreed, making them among the few curators “willing to go out on a limb” for the artist back then, Greenan recalled.

For the MCA’s director Madeleine Grynsztejn, the show “was a no-brainer,” Beckwith said. And when “Madeline says, “of course’ like that [to a show], that also means she sees the fundraising possibility. She sees the press.”

According to Grynsztejn, she saw it as “an opportunity for an exhibition which while not in any way predicted to be a ‘blockbuster,’” she explained, “but had to be done for mission reasons.”

Because for a long time, a show like that one wasn’t a part of the MCA’s mission.

The Museum of German Art

When Beckwith was a kid growing up in Chicago, a lot of people would call the MCA “the Museum of German Art,” she said. It was founded by a group of local art enthusiasts who wanted a kunsthalle-type institution to show edgy work “of the now.” The shows were innovative, but not very diverse.

By the ‘90s, though, that had already started to change. Chicago-based dealer Monique Meloche worked at the museum from 1991 to ‘97, and noticed that it had “diverse practices already in place back then.” They acquired works by artists who were new to many in the early ‘90s: Adrian Piper, Lorna Simpson.

For the decade preceding Darling’s tenure, Elizabeth Smith was the MCA’s chief curator. During that time, the museum brought in—often in conjunction with exhibitions—pieces by artists including Gillian Wearing, Jenny Holzer, Kara Walker, and Glenn Ligon, along with many local artists.

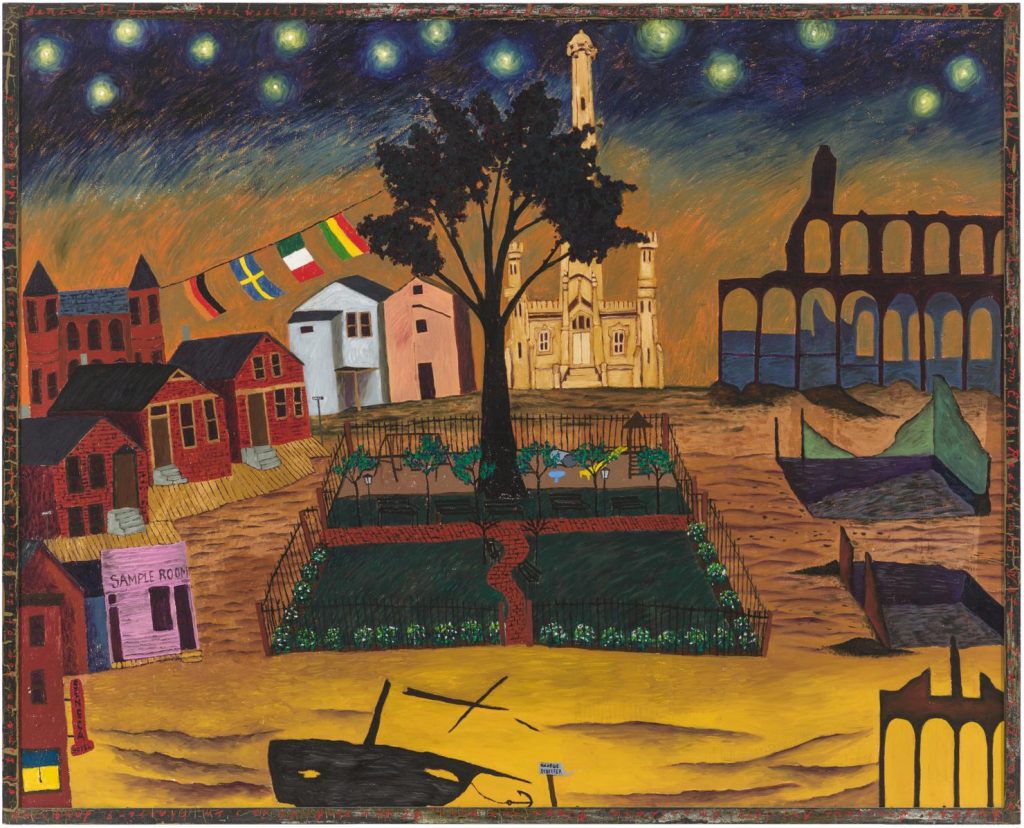

In 2003, the MCA organized one of the first major shows of Kerry James Marshall’s work. After Grynsztejn became the director in 2008, she proposed a full-scale retrospective. “Kerry James Marshall: Mastry” went on to travel to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, becoming the defining show of the artist’s career (as well as a huge success for all three institutions).

“I think what we built up during that time,” Smith said, “provided a good foundation for what came later”: a more formalized commitment to diverse practices.

Changing the Game

In grappling with what it meant to diversify in even more meaningful ways, the MCA had to figure out how to actively change what it was known for. That started with building a curatorial team that was international and committed to diversity.

While that alone doesn’t guarantee that any museum will present a fully decolonized art history, the MCA, for one, “wouldn’t have hired me if that wasn’t the agenda,” Beckwith said—particularly with respect to her “thinking about Blackness in the most expansive way possible.”

Then came the strategy.

When Darling first started at the MCA in 2010, he’d line up ideas for shows on the calendar. And if it showed “two male artists in a row,” he said, “or two white artists back to back,” he’d flag it as unacceptable.

After “a long tail of successes,” he continued, “with these major survey shows of women artists,” in particular, the museum started to fundraise on a gender-parity agenda around 2015—and later formalized that commitment by creating the Women Artist Initiative (a fundraising platform supporting exhibitions, acquisitions, and programs of women-identified artists) in 2020.

From 2015 to 2022, Grynsztejn said, “we have represented 28 solo exhibitions—more than 50 percent of our program—as women-identified.”

At the MCA, exhibitions and acquisitions are closely linked; the museum often acquires art from its shows. Work by Andrea Bowers, Christina Quarles, and Camille Henrot, who have all had solo shows there, are part of the 54 percent of artworks by women-identified artists that the MCA brought in since 2020.

The MCA’s collection committee meets three times a year and is “presented with a slate of 10 to 12 works that reflect [a course-correcting] roadmap,” said Grynsztejn. Another acquisition body, called Emerge, also prioritizes work by women and artists of color.

“The real agency comes from the purchases,” said Darling, “and using the museum’s actual funds to go out and buy those artists of color.”

As Grynsztejn likes to say, “it takes two villages that are in lockstep” to make these changes happen: “It takes a staff and then it takes the donor community.”

The Flywheel Effect

When curators move on, their diversity agendas sometimes leave with them. But after Darling and Beckwith left (Beckwith to take over as deputy director at the Guggenheim, and Darling to found a startup called Museum Exchange), the MCA recruited René Morales, previously the director of curatorial affairs at the Pérez Art Museum Miami—which has its own solid record in collecting the work of diverse artists, according to the Burns Halperin Report—as chief curator. Studio Museum and ICA L.A. alum Jamillah James was hired as senior curator.

Just as the curators before them did, they will have to work to generate the support they need to bring about change.

But they are inheriting an already changed institution. As COO Gwen Perry Davis notes, the MCA has been “thoughtful about working with donors who are inclined to give us their objects, and perhaps help us purchase gifts about what we’re interested in and what our commitment is.”

While working in the development office, one of Davis’s roles was to diversify the board, which resulted in more women and people of color as trustees. The evolution in the museum’s programming “also led to an increase of Black trustees on our board to 8 percent versus less than 6 percent nationally,” said Grynsztejn.

And as curators continue to introduce museum supporters them to work by artists they may not know (while also being “judicious if you’re dealing with someone whose collecting practices don’t align with the current mission of the institution,” Beckwith said, “to bring them along with you”), their own collecting practices often begin to evolve.

To Grynsztejn, these internal negotiations reflect a flywheel effect—when small wins build on each other over time. Because the hope is that as these collecting practices change, the gifts the museum receives down the road will as well.

Recently, the institution received a donation from a trustee that added 24 works to the MCA’s holdings of global women artists active after 1970, including examples by Kiki Smith, Ghada Amer, Marina Abramovic, and Sarah Lucas. It was “our explicit commitment to gender equality that got [the donor’s] attention,” noted Grynsztejn.

Because the fact of the matter is: gifts (as opposed to purchases) end up defining an institution more than anything else.

And those gifts are “often by white artists and or male artists,” Darling said, “so it’s a really big challenge for museums to actually turn those numbers.”

The Hard Truth

A few years into her tenure at the MCA, Beckwith actually ran the numbers, and “I saw what looks like not-encouraging percentages of artists of color…of anyone considered non-white,” she said.

And when she was talking about that with her husband, a self-proclaimed “numbers person,” she recalls him saying, “Well, if you have a massive number of objects—which is around 3,000, and you’re only bringing in annually, like 20 or 30 objects, the needle doesn’t move that much…even if it’s like 100 percent non-white that year.”

And some museum acquisitions are restricted, meaning you can’t deaccession or streamline them to tilt those percentages.

In that way, if it took the MCA “75 years to build up a 90 percent white collection,” she continued, at that rate, “it’s going to take 75 more just to get to parity, not even majority…this is going to be bigger than me in my lifetime.”