From childcare benefits to a reworked board structure, these measures have made a difference across the corporate world.

By Tim Schneider, Artnet News’ Art Business Editor

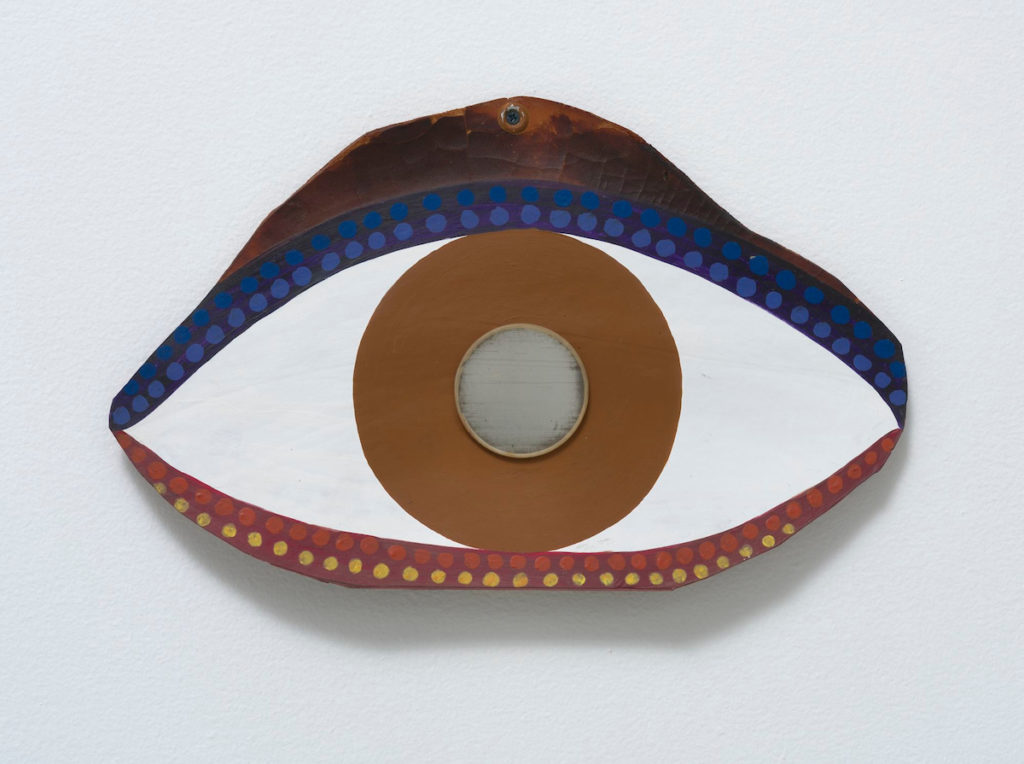

Betye Saar, Eye (1972). Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Tilton, Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

Betye Saar, Eye (1972). Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Tilton, Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

The 2022 Burns-Halperin Report does vital work by quantifying the (distressing) degree of inequity among different demographics of artists in U.S. museums, global auction houses, and commercial galleries. Data-led research is often necessary to prime any industry to make meaningful change, and the art world needs a nudge more than most.

But what types of shifts would have the biggest positive impact on longstanding DEAI problems? What concrete initiatives and policies have been most effective elsewhere in the economy? And which of them are even achievable in the niche realm of the arts?

Answering these questions requires a bit of context. Some museum insiders say that institutions already over-index to corporate America as a role model, and that more useful examples should be sourced from activist groups or the education sector. At the same time, they also acknowledge that the language of business is the language that trustees are most ready to listen to. (The same holds true for most for-profit art sellers, too.) And since it’s a tall order to implement significant organizational changes without the buy-in of top stakeholders, looking to the private sector has distinct advantages.

Some decision-makers still fall back on the narrative that the arts are too special a case for other businesses’ successes to apply. Even the difference between what would work on the for-profit side of the art trade and the nonprofit side is substantial enough to short-circuit universal action plans.

Other experts who know better disagree.

“There is no difference,” said communications and social-impact consultant Susan McPherson, who advises clients across industries. “Organizations, companies, nonprofits, museums—they’re all made up of people, and people are all made up of values.”

To that end, we examined five DEAI measures taken by other industries to consider how they could be applied to the nonprofit and for-profit sides of the U.S. art economy alike.

Not all are suitable for every size and scale of workplace. Some only make sense for employers with dozens or hundreds of staff members. But others are viable for even the smallest entities, and thinking about the rest in advance would be wise for any art leader with aspirations to build a long, successful career and a diverse, equitable, and inclusive work environment.

1. Hire—and Truly Empower—DEAI Executives.

The Concept:

Becoming a genuinely diverse, accessible, and inclusive organization is a complex and important goal—so complex and important that companies or institutions beyond a relatively small size can only accomplish it with guidance from people dedicated to it 100 percent of the time. Enter the DEAI executives, who are responsible for designing and overseeing a comprehensive, ongoing plan for integrating progressive values into every aspect of the entity.

The Context:

The art industry is still further behind most others on this front, but perhaps less so than you might expect. DEAI executives were a rarity in corporate America as recently as the beginning of 2020. But in the immediate aftermath of George Floyd’s murder by police (and the coast-to-coast civil-rights uprisings that followed), for-profit and nonprofit entities in a variety of fields raced to hire professionals with experience in building universally welcoming, supportive workplace cultures. The still-unanswered question in most cases is how many of these hires were simply a short-term PR strategy rather than the cornerstone of evolved practices that will stand the test of time.

The Caveats:

Experts stress that it isn’t enough for a company or nonprofit to hire a DEAI executive. The true tell is the structure of the position and the resources granted to it. Who does the DEAI executive report to? What kind of a budget do they have? Are they empowered to hire a team, or are they expected to do the job alone?

Siloing a DEAI executive within the human resources department sends a message that leadership sees the underlying issues as being entirely about hiring, policing, and when necessary, firing personnel. This limitation is more likely to breed suspicion and mistrust than comfort and cooperation. A DEAI head who reports directly to the CEO or the board, however, is much more likely to be seen as an empowered ally to rank-and-file staff, and therefore to usher in the kind of holistic shift they were ostensibly brought in for.

Remember This:

Latasha Gillespie, the global head of diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives for Amazon Studios, summed up the realities of DEAI leadership as follows in the Hollywood Reporter in 2021: “You cannot hire one person and expect them to change an organization… If you’re not ready to staff them up with a team and give them resources and a budget, it’s performative, disheartening, and you’re setting that person up for failure. Usually that person is a woman, from an LGBTQ community, or a person of color, and when it doesn’t go well, then that person is the problem, not the organization. It’s dangerous.”

2. Establish Diversity Quotas for All Staff Positions.

The Concept:

Although a comprehensive DEAI strategy is about much more than just hiring more diverse and inclusive staff, hiring more diverse and inclusive staff is still a necessity. One mechanism to spur change is to establish interview and hiring quotas for applicants from historically underrepresented demographics. The optimal version of this policy also involves publicizing (at least, among all staff) and continuously reevaluating those numbers over time.

The Context:

Diversity quotas tend to be used most often when it comes to filling upper-management, if not executive-level, positions, but an enlightened employer can and should implement them across the org chart. They are perhaps the most common sense, achievable step an art-world employer of any size can take to level up its DEAI game.

Perhaps the most well-known manifestation of the diversity quota in U.S. business is the so-called Rooney Rule, a provision in the National Football League’s collective bargaining agreement that no franchise can hire a head coach, player personnel czar, or other executive without first interviewing at least one candidate of color for the job. Crucially, the requirement has teeth: any suspected skirting of the Rooney Rule (named after deceased Pittsburgh Steelers chairman Dan Rooney, who championed the policy) is investigated by the league commissioner’s office through a white-show law firm. Parties found in violation can be fined millions of dollars and/or stripped of one or more upcoming draft picks.

The Caveats:

The NFL is an incredibly specialized business, and its traits make the Rooney Rule (and quotas generally) a challenging template for the art world to follow. The main questions that would need to be answered are: How would diversity quotas be enforced? By whom? Under what conditions, and with what penalties awaiting bad actors?

In the U.S., there is no specific oversight body governing either the nonprofit or for-profit sides of the art industry. The only pseudo-regulatory structure comes in the form of voluntary professional associations such as the Association of Art Museum Directors, Alliance of American Museums, and Art Dealers Association of America. These bodies could police diversity quotas in theory, as the AAMD (in)famously polices deaccessioning practices. But their member organizations would first need to hammer out a shared policy, including agreeing to be permanently monitored and punished when necessary—all of which seems unlikely.

It’s also notable that the Rooney Rule hasn’t even worked particularly well in the NFL during its 20-year lifespan: in February 2022, only three of the league’s 32 franchises employed head coaches who were not white men, despite only about 30 percent of players hailing from that demographic. (Four of the jobs were vacant at the time.)

Remember This:

One counter to the caveats above could be to try to incentivize good behavior rather than to try to disincentivize bad behavior. McPherson pointed out that some entities tie key managers’ and executives’ compensation to surpassing staffing quotas and other objectively defined DEAI goals. This approach could help square the circle in the thinly regulated art industry.

3. Diversify the Makeup of the Board (and Not How You Might Think).

The Concept:

Boards of trustees hold tremendous power over the direction of museums and large corporate entities, yet tend to overwhelmingly be made up of similar people with similar values, skills, and thought processes. Most often, wealthy, college-educated white people predominate. For an entity to meaningfully move forward on DEAI issues, its board membership must embody the changes that the organization wants to see. That means adding new faces to the boardroom.

However, rather than bringing in similarly high-powered, high-net-worth professionals who also happen to be, say, women and/or BIPOC, a more meaningful move would be to elect new board members who are still a part of the often-underserved groups that any organization committed to DEAI principles should desperately want to welcome and empower. Museums, in particular, could add trustees from their various publics, including local community leaders, progressive activists, and even their own staff.

The Context:

To put it bluntly, no matter their individual ethnicities or gender identities, a room full of CEOs, private-equity titans, and corporate attorneys is still a room full of CEOs, private-equity titans, and corporate attorneys. Not everyone who holds these types of jobs will automatically be a staunch defender of the status quo, but there is a high probability that people in similar financial and professional contexts will share fundamental values about how businesses should be run, how money should be spent, and who should have a say in those matters.

This is why the types of diversity most likely to push boardrooms forward could be diversities of skill, class, education, and community involvement. By working with people from these types of societal cross-sections, trustees from traditionally elite contexts would need to grapple with perspectives from which they are often insulated—a challenge likely to be as full of discomfort as it is full of potential.

One intriguing model is Germany’s corporate-governance law. For any German company that employs more than 500 people, one-third of the seats on that company’s supervisory board must be made up of staff members voted in by their colleagues. For any German company that employs more than 2,000 people, the share of board seats required to be held by popularly elected staff rises to half.

The mechanism ensures that the voices and interests of employees wield significant power where overarching decisions are made. Art-world boards could adopt this example with minor tweaks but could also apply its spirit to bring in trustees from some of the other atypical demographics mentioned earlier.

The Caveats:

Although there has been some recent discussion around the need to change the composition of museum boards (Ford Foundation president Darren Walker has been publicly advocating for it for years), there is still relatively little understanding in the wider art world of how boards operate and are structured. The realities dramatically increase the difficulty of revising the ranks of trustees.

Nearly all boards observe formal bylaws. This means making major changes, such as editing the number of seats or the identities of the people who hold them, need to go through a formal approval process controlled by the current board. It’s not hard to see the problems here, especially since relatively few institutions’ bylaws include term limits on trusteeships. As a result, restructuring boardrooms would require not just extreme self-reflection among existing trustees, but also very real abdications of power.

Remember This:

Some museums have tried to make progress on this front in recent years by adding one or more artists as trustees—most often to act as a sort of moral compass. Yet museum insiders say that the nature of such positions have tended to quickly burn out or repel artist-trustees, as when a quartet of star artists resigned en masse from the board of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles after the 2012 firing of chief curator Paul Schimmel.

4. Create—and Support—Employee Resource Groups.

The Concept:

An employee resource group (ERG) is a voluntary organization of staff members inside a given workplace who share an identity or lifestyle trait. Each ERG serves as a combination of social haven, career enhancer, and advocacy group for its members. They provide employees in minority demographics with human connection among kindred spirits, professional-development training, and proactive allyship on DEAI-focused policies like equitable compensation, dispute mediation, and anti-discrimination.

Although it is optional for employees to join ERGs, the groups are officially recognized by their employer. In the best cases, the employer may even set up a DEAI council to coordinate between the various ESGs under its roof.

The Context:

“You could hire a ton of people of color and they could not feel welcome, and then they’re out the door in no time,” McPherson noted. ERGs can be an important retention mechanism by reinforcing a workplace’s larger commitment to DEAI in arguably the most personal—and light-lift—way.

Corporations across industries have bought into the strategy. AT&T hosts 26 different ERGs that together connect nearly 90,000 employees. Google has created at least 16 different internal resource groups (and counting) with more than 250 chapters representing 52 countries and more than 35,000 staffers. The groups are based on everything from ethnic heritage (see: the Black Googler Network) and age group (see: Greyglers, for employees in the latter stages of their careers), to gender identity (see: Trans@Google) and religious faith (see: Google’s Inter Belief Network), and more.

The Caveats:

Long-term viability of ERGs in a workplace hinges on the same variable as long-term employment of individuals from diverse demographics: genuine good-faith engagement from management. If a resource group feels its concerns are going unheard, it is likely to disband. Its constituents are also likely to start looking for work elsewhere soon after, or even before, that happens.

5. Include Childcare Benefits as Part of Employee Compensation Packages.

The Concept:

No country (and no art market) in the world has a larger delta between its income level and its near-absence of government-mandated family benefits than the U.S. Since childcare disproportionately falls on mothers, American workplaces committed to gender diversity could gain a major advantage by making it standard operating procedure to underwrite or provide childcare services for all staff. Commercial galleries could even do the same for women artists they represent.

The Context:

Women’s participation in the U.S. workforce has always been adversely impacted by the demands of parenting and the nation’s political disregard for its importance. But the effects have been especially damaging since the COVID-19 lockdowns of 2020, and studies show that costs and obstacles to childcare are a major reason why. (A rare glimmer of positive change was snuffed out at the end of 2021, when a deadlocked Congress allowed an incredibly effective pandemic-era child tax credit to expire.) No wonder a recent McKinsey & Co. survey found that nearly 70 percent of responding women said that employer-sponsored childcare benefits “could sway their decision on where to work.”

A growing raft of U.S. companies are stepping up, from financial-services giants like Goldman Sachs and Bank of America, to tech companies like Microsoft and Intel, to retailers like Patagonia and Best Buy. There is no reason that well resourced art businesses couldn’t follow their lead.

The Caveats:

Offering automatic childcare benefits is a prime example of the type of policy shift only likely to happen after a broader DEAI awakening takes hold within a workplace. As long as the majority of chief decision makers are men feeling little to no pushback within their organizations, this game-changing perk will probably be viewed as an unnecessary expense. Why should they be proactive if none of their competitors are doing it?

Remember This:

Research consistently backs the conclusion that childcare benefits improve not just the culture but also the level of innovation and the bottom-line results of the workplaces that provide them. The same is true for the other four action items above.

Rather than a generational nicety, a thoughtful, holistic DEAI strategy proves over and over again to be good business across economic sectors. It’s past time for the art industry to put their money—and their practices—where their mouths have been.